Plain Text Accounting with Emacs

For a while I have been concerned that I haven’t really been on top of my finances as well as I should be, and I decided to bite the bullet and do something about it. I’ve been looking to get much better visibility into my share portfolio, and make sure I track it properly so that if I sell any shares I can easily calculate captital gains and such at tax time. I am also keen to get a better idea of my spending patterns so that I can see where I may be wasting money.

Since I have been having lots of fun recently diving into Emacs Org, I did some research on whether it may be helpful in getting a better handle on my finances. After a bit of research, I started to realise that Org mode may not be the best tool for what I was looking to do, but I saw a number of people talking about using a program called Ledger, which takes as input plain text files describing your finances, and then crunches the data to produce various reports. Since the data is managed using human readable text files (“accounting journals”), Emacs can be used as the text editor of choice, and there is even a “Ledger mode” in Emacs to handle all the usual syntax highlighting and auto-completion you would expect in any text-based specification language.

Choosing a Plain Text Accounting Tool

It seems there is an enthusiastic community using a variety of tools such as Ledger to track their finances using plain text files. One of the main hubs is the website https://plaintextaccounting.org/ . This website talks about some of the basic concepts behind accounting, and mentions the various tools that are available. So, my first task was to work out which tool I should use.

- Ledger is the oldest cli-based tool, and has the most features. The journal format is fairly forgiving and widely used, and Emacs has a Ledger mode..

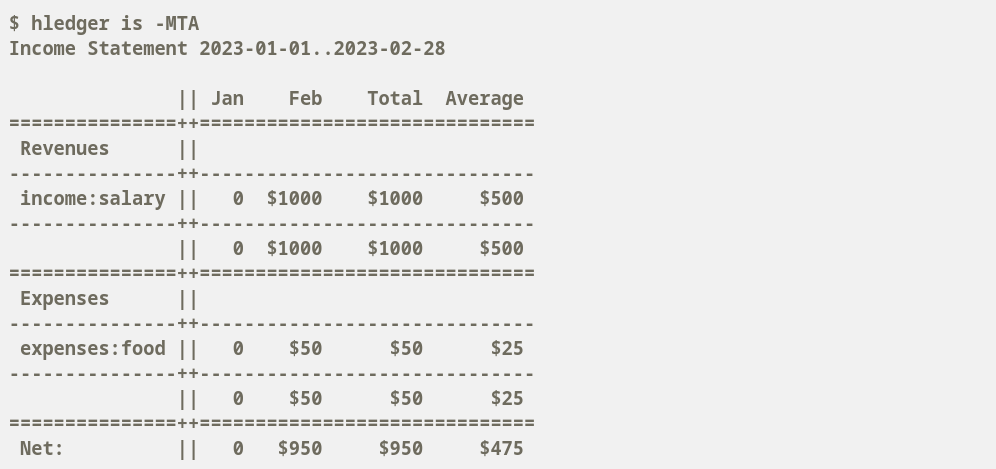

- HLedger is a more modern rewrite of Ledger, written in Haskell. The developer has tried to “clean up” some of the idiosyncrasies of Ledger and streamline the tool. It is missing some of the features of Ledger, but the developer explains how to handle some common use cases using the simpler feature set. It appears to be more actively developed that the other plain text accounting (PTA) tools. Emacs also has an HLedger mode.

- Beancount is written in Python, and uses a different format for its journal files than Ledger and its derivatives. The formatting of the journal is stricter than the other tools.

- GNUCash is a GUI-based application which uses an SQL database for the persistent data store. This is not plain text accounting software at all, but I thought I would look into it anyway to see if it might be a better fit for my use cases.

After looking into these 4 tools, I decided that I really did want a plain text accounting journal that I could put under version control using Git/Magit. GNUCash seemed a bit heavy handed for what I want to do. I am not running a complex business; I am just earning a salary, doing some share trades, and trying to keep my spending under control. For something simple like this, a text file is fine, especially since I am already making heavy use of text files through Emacs/Org mode. In the end, I decided to go with HLedger:

- it is more up-to-date, and lacks the historical quirks and missteps of Ledger

- the file format is forgiving, and because it lacks some of the complexities of Ledger, I believed it would be quicker to pick it up.

- it is written in Haskell, which sounds like an interesting language that I might learn more about if I want to write any customisations.

- if I want to look further into Beancount, then there are conversion tools that can help to migrate to the different format.

Basic Accounting Terms

Having selected a tool, the next thing was to look into how accounting works. These PTA tools are all based on the idea of double-entry book keeping. I don’t want to go into detail here about double-entry bookkeeping, as others have done it better than I could. I recommend you read the introductory article on the plaintextaccounting.org website. In a nutshell though:

- Money is tracked by putting it into and taking it out of accounts.

- There are 3 types of accounts that store value: Assets (things you own), Liabilities (things you owe to other people) and Equity (this is complicated, but at a simple level it is a measure of money you have invested in the vanture).

- There are 2 more types of accounts that represent money entering or leaving the venture: Revenue (money coming in from an outside source) and Expenses (money you pay to out to someone else).

- If you take money out of one or more accounts, you need to put that same amount of money into one or more accounts. From a physics perspective, this is something like the law of conservation energy – money cannot be created out of thin air, it can only be transferred from one place to another.

Setting up HLedger and HLedger-mode/Ledger-mode

There is no magic here, I just installed hledger using my package manager, in my case:

pacman -Sy hledger hledger-ui hledger-web

The last two packages are optional.

hledger-uiis a text-based user interface (TUI) for hledger. The range of reports it can do is limited compared to what can be done with the hledger command line tool. It is however a convenient way to look at standard information such as balance sheets and income statements.hledger-webprovides a mini web service that implements a web GUI. I haven’t looked into this at all, since I am mainly interested in sticking with text reports/Emacs.

To install hledger mode on Emacs, you can follow the instructions on the developer’s github . I haven’t looked into it very deeply, and I’m now thinking that Ledger mode on Emacs may even be a better option than hledger-mode:

- ledger-mode comes pre-packaged in the Doom Emacs distribution that I am using.

- it seems to have some nice features such as M-q to align your currency amounts. To see what I mean, check out this demonstration of Emacs ledger mode from EmacsConf 2019.

I will need to explore this further.

Creating Journal Entries

Ledger is quite flexible in the way you use it. You need to give some thought as to what sorts of things you want to track. There are cookbooks available that suggest different ways to structure your entries. As an example, I wanted to track my salary income. At a very simple level, you can record when you see your salary credited to your bank account:

| |

This transaction takes $2000 from my employer (a source of revenue or income), and puts it into my savings account. With double entry accounting, the amounts within the transaction always need to sum to zero, which is why we have two amounts of equal and opposaite sign. If you try to enter an “unbalanced” transaction, the system will complain, and you will need to fix the transaction so the amounts add to zero.

Because this rule must always hold, it is possible to leave one of the amounts blank, and the system will deduce what amount needs to go there so everything adds to zero:

| |

I then decided that I wanted to track how much tax the employer had removed from my pay packet, and how much they had contributed to my superannuation account. Also, the date on which I get my payslip may not be the same date that the money actually goes into my account. For more flexible reporting, I can do something like this:

| |

Here, I can track in the expenses:taxes:withholding account how much money the employer sent to the tax office. Whatever is left over temporarily goes into an account called assets:receivable:salary. This is an asset, because the employer owes me money. However, I don’t want to record it as going into my savings account until the employer actually transfers the money there. Once they do that, I then create a second transaction where the money is transferred out of that holding “Receivables” account and into my savings account on the date that the transfer actually happens. If for some reason the transfer doesn’t go through, then I can run a report to show that I have some money sitting in “Receivables” that hasn’t found its way to my account yet, and I then know I need to follow up with my employer. Similarly, I can track the compulsory contributions that my employer must by law make to my superannuation account, and I can reconcile at the end of the year when I receive the end-of year report.

Entering in more data

Having grasped the basics of how the accounting tracks the flow of money through different accounts that can then be reported on, I went through and entered all the transactions I have made for this past financial year. There was a lot of data to enter, which was quite time-consuming, but it was a useful exercise because it made me examine my finances in detail. It was particularly helpful for share trades, where I needed to trace what had happened with mergers and takeovers and investigate the tax office rulings that I would need to follow should I decide to sell any of those shares.

I’ll talk a bit more in a future article how to download market price data and how one can trace the capital gains of various share lots that one may have purchased at different times, and perhaps look at some of the reports that can be used to help understand where one stands financially.

Conclusion

This has been a fun exercise where I have learned a lot about accounting, and also made some surprising discoveres such as how much I spend on coffee each month! I feel I am in a much better position to make better financial decisions, and it is nice to know that at tax time I will already have the key information available at my fingertips without having to trawl through mountains of paper. Entering a little bit each day is certainly preferable to letting everything pile up to be dealt with in a flurry of activity at Year End. If you want to become better organised, I suggest looking into these types of tools. You can make it as simple or as complicated as you like, and you will definitely learn something about managing money.